Book Excerpts: This page has Chapter 10 followed by Chapter 23

Chapter 10: The Fictitious War on Marijuana

In the lead-up to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, a University of Maryland study found many Americans held three incorrect beliefs that made them support the war. They believed that Iraq’s leader was involved in the September 11, 2001, attacks, that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and that most of the world supported the war. And the press reinforced these beliefs. As a result, the United States started a war that most Americans later decided was a mistake. (1)

We’re now repeating that error with drugs. The marijuana lobby has painted a picture of aggressive police and an out-of-control legal system bent on punishing harmless drug users. As a result, many people have three false beliefs:

1. They believe the War on Drugs is a war on otherwise innocent drug users.

2. They believe prisons are full of people whose only crime was to use marijuana.

3. They believe police zealously and intentionally pursue individuals who use drugs.

Not one of these beliefs is true.

.

.

1. The War on Drugs was never a war on drug users

In 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon launched the War on Drugs with increased spending to enforce the law against distributors of illegal drugs, not against drug users. He was the first U.S. president to see drug addiction as an illness, and he called for treating substance abuse instead of simply criminalizing it. He thought mandatory minimum sentences for simple possession were immoral, and in 1971 he got rid of federal mandatory minimums for marijuana and other drugs. (2)

At the time, the country’s main drug problem was heroin addiction. In his message to Congress, Nixon said:

“I am proposing the appropriation of additional funds to meet the cost of rehabilitating drug users, and I will ask for additional funds to increase our enforcement efforts to further tighten the noose around the necks of drug peddlers, and thereby loosen the noose around the necks of drug users. At the same time I am proposing additional steps to strike at the ‘supply’ side of the drug equation—to halt the drug traffic by striking at the illegal producers of drugs, the growing of those plants from which drugs are derived, and trafficking in these drugs beyond our borders.” (3)

Nixon’s plan was to have tough law enforcement against major traffickers, and more treatment for users. Of the $155 million he requested, two-thirds was to be spent on drug treatment. The rest was spent pursuing large, overseas drug traffickers such as the “French connection.” The man Nixon put in charge of the drug war, a psychiatrist named Dr. Jerome Jaffe, was a pioneer in devising programs to help inner-city drug addicts. The main weapon in the war on drugs was treatment, not arrest or incarceration. Jaffe and the Nixon administration opened methadone clinics across the country, and those clinics are still the most effective treatment for heroin addiction. To help addicts, the Nixon administration even gave financial support to the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, a symbol of the counterculture that was largely funded by the Grateful Dead. (4)

The legalization lobby says the drug war “failed,” but under Nixon it was successful; deaths from drug overdose dropped significantly in most large cities, and so did crime. Drugs remained illegal, but the focus on treatment worked. (5)

So how did our image of the War on Drugs mutate into its exact opposite? Why do so many people believe Nixon used the police to target drug users? And how did the drug war get linked in the public mind to mass incarceration?

For the answer, we need to look at laws passed a decade later under President Ronald Reagan. These Reagan-era laws increased prison time for all types of crime. As a result, the incarceration rate increased, but most of this increased incarceration was for non-drug crimes.

However, the marijuana lobby conflated Nixon’s drug war with the Reagan-era “lock-’em-up” policies and told everyone that drug laws caused prison overcrowding. And they repeated it so often that many people now believe it.

Here’s what actually caused incarceration to skyrocket. In the 1980s and early 1990s, conservatives pushed through tougher penalties for all types of crime, not just drug crime. Lawmakers believed longer sentences would keep dangerous criminals off the streets. So nearly every state increased the length of prison terms for all types of crime. Some also passed persistent felony offender laws—a.k.a. three strikes laws, which locked people up for life after their third felony, no matter how minor. (6)

Several states and the federal government abolished parole, forcing inmates to serve entire sentences. And in the 1980s, Congress passed federal sentencing guidelines and established mandatory minimum sentences for several crimes. Many states also passed mandatory minimums. (7)

Crime prevention suffered. Nixon spent most of the drug war money on treatment because that was the best way to prevent crime. Under Reagan, money for treatment was slashed and law enforcement increased. In inflation-adjusted dollars, the 1986 federal drug treatment budget was only one-fifth of what it had been in 1973. (8)

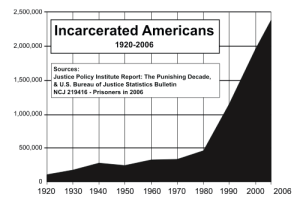

Under President Reagan, the United States all but stopped trying to prevent crime and instead relied on locking up criminals for as long as possible. As a result, the U.S. prison population climbed by more than 400 percent. As this graph shows, mass incarceration started under Reagan, not Nixon. (9)

Most of the mass incarceration had nothing to do with drug crime. According to the Pew Center on the States, between 1990 and 2009, the average length of time served increased by 37 percent for violent crimes, by 36 percent for drug crimes, and by 24 percent for property crimes. (11) All types of crime contributed to prison overcrowding.

In particular, neither Nixon’s War on Drugs nor laws making drug possession illegal caused mass incarceration. In fact, Michael Massing, author of The Fix, said the United States could undo the damage by abandoning the Reagan-era laws and going back to Nixon’s policies. (12)

One former White House policy advisor believed Nixon only used the draconian term “war on drugs” to appease his party’s right wing, conservatives who thought providing treatment was just coddling criminals. (13) Unfortunately, people remember the military-sounding language, but not the actual plan, which might have succeeded had it not been mostly jettisoned under Reagan. The sad story of the drug war is that it went from mostly treatment to mostly interdiction overseas, which is far less effective. However, it was never about criminalizing drug users. There was never a war on drug possession.

How the marijuana lobby redefined the drug war

Pro-legalization groups wanted to vilify drug laws, so they rewrote history; they used the term “drug war” to mean laws against possession. This allowed them to create a very compelling myth: The drug war, they said, is the intentional pursuit and mass incarceration of innocent people whose only crime was to use drugs, filling our prisons to unheard-of levels. They could then say the only solution to mass incarceration is to end the drug war by legalizing drugs.

It’s a fiction that mischaracterizes the drug war and misstates the reason for prison overcrowding, but the marijuana lobby repeated its version over and over until nearly everyone believed it. And they’re still trying to convince us.

- This is from the Drug Policy Alliance website: “the United States imprisons more people than any other nation in the world—largely due to the war on drugs.” (14)

- On the ACLU website, one page had the sub-heading: “Campaign to End Mass Incarceration.” Below that, the ACLU wrote, “Here’s our list of what needs to be done,” and first on the list was “End the War on Drugs.” (15)

- Here’s a quote about prison overcrowding from the Marijuana Policy Project: “We don’t really need congressional hearings to determine where those millions of prisoners come from. Many are nonviolent drug offenders—disproportionately poor and African-American. Nixon declared war on them more than three decades ago, and we’ve been paying for it ever since. Nixon’s favorite drug war target, of course, was the marijuana user.” (16)

The implication in these statements is untrue. Most people in U.S. prisons were convicted of non-drug crimes, so even if we freed everyone imprisoned for a drug crime, we’d still have mass incarceration. (17) And Nixon did not target marijuana users. Just the opposite; he eliminated mandatory minimum sentences for marijuana possession. He was the first president to view drug use as an illness rather than as a crime. So, vilifying Nixon for a time he was sensible and compassionate seems especially unfair.

However, Nixon’s dishonesty is legendary, so there’s poetic irony to the marijuana lobby twisting the public perception of his drug war into its exact opposite. (18) If anyone could appreciate how crafty the marijuana lobby has been, it would be Richard Nixon.

.

.

2. Incarceration solely for marijuana possession is incredibly rare

On its website, NORML has an article titled “Decriminalizing Pot Will Reduce Prison Population.” The article said decriminalizing drugs, along with “modest reforms in sentencing and parole,” could cut the prison population in half.19 In a Washington Post op-ed, Katrina vanden Heuvel said that legalizing marijuana would “drastically decrease incarceration rates.”20

Is this true? If we decriminalized marijuana and stopped prosecuting people whose only crime was simple possession, would it significantly decrease our prison population?

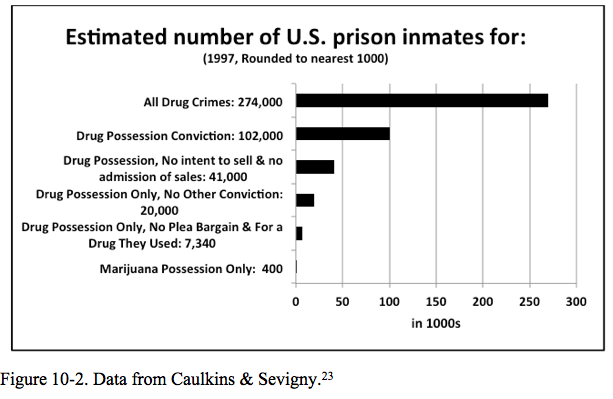

Two researchers set out to answer this question. In a paper published in Contemporary Drug Problems, Jonathan Caulkins and Eric Sevigny looked closely at Bureau of Justice Statistics reports for 1997. In that year, 274,324 state and federal inmates in the United States were in prison for drug crimes. That was 24 percent of all inmates. Most of these inmates were in prison for selling drugs, but 102,232 inmates—or 9 percent of all inmates—were convicted of drug possession.21

Normally that’s all the information the Bureau of Justice Statistics provides, and pro-legalization groups use this data to claim that prisons are packed with people whose only crime was using drugs. However, in 1997, more than 18,000 inmates were interviewed as part of a state and federal multi-prison survey. Caulkins and Sevigny used the data to estimate how many inmates were truly guilty of nothing more than possessing drugs for personal use.

They made a serious effort to identify those inmates arrested for their role in drug trafficking or for a crime that had nothing to do with drugs. As they wrote in their article, the question they wanted to answer was, “How many people are imprisoned in the United States for drug-law violations simply because they used drugs, not because they played some role in drug distribution or other offenses?”

They found that many of the 9 percent of inmates in prison for possession were actually convicted of possession with intent to sell. Many others admitted in interviews that they’d been selling drugs. And many more were caught with such large amounts that it was clearly not for personal use. Police often claim that they use possession charges when they don’t have enough evidence to make trafficking charges stick, and evidently this is true.

When the researchers excluded all the inmates who had clearly been selling drugs and not just using them personally, it left an estimated 41,047—3.6 percent of the nationwide prison population—who were incarcerated for simple possession and, according to the researchers, “not clearly involved in drug distribution.”

When the researchers looked further, they found that half of that 3.6 percent had committed a non-drug crime along with drug possession and were in prison for both. For example, they were in prison for burglary and drug possession, or assault and drug possession. These people all had other reasons besides drugs for being in prison. So the researchers excluded all those people, which brought the estimated number of inmates convicted only of simple possession down to 20,479, or 1.8 percent of all inmates.

Then the researchers dug even deeper, looking at more data on these possession-only inmates. Half of them were convicted as part of a plea bargain. They pleaded down from a more serious crime or from multiple counts. So they pleaded guilty to possession, but they’d been arrested for something else, such as for selling drugs or for a violent or property crime.

Approximately one-quarter said the drug they were in prison for was one they themselves didn’t use. That’s a common story among drug dealers. A lot of people who sell meth and heroin know better than to use those drugs themselves.

The authors therefore excluded inmates convicted of possession as part of a plea bargain or who said they never used the drug they were convicted of possessing. That brought the estimated number of people in prison solely for possession of drugs down to 7,340, or 0.6 percent of all state and federal prison inmates.

Lastly, the authors excluded everyone who had been arrested for selling drugs in the past or who admitted to hanging out with friends while they were selling drugs. That brought the estimated number down to 5,380, or 0.5 percent of all prison inmates.

To sum it up:

- 274,324 are in prison for drug crimes. Of those in prison for drug crimes,

- 102,232 are in prison for possession with no trafficking charge. Of those,

- 41,047 are in prison for possession with no obvious evidence of drug sales. Of those,

- 20,479 are in prison for possession only, with no other crime and no evidence of drug sales. Of those,

- 7,340 are in prison for possession only with no plea bargain, no other crime and no evidence at all of drug sales. And, of those,

- 5,380 are in prison for possession only with no plea bargain, no other crime, and no current or past evidence of drug sales.

And that’s possession of all drugs. Most people in prison for possession are there for heroin, cocaine, or crystal meth. In this study, the authors found only 5–7 percent of those people were in prison for possession of marijuana. Taking 7 percent of 5,380 gives approximately 377 inmates incarcerated solely for possession of marijuana.

So, rounding up, approximately 400 people, or 0.05 percent of all prison inmates, were in U.S. prisons solely for the possession of marijuana in 1997. That’s one-third of one-tenth of 1 percent of the prison population.

That’s the lowest possible estimate based on their data. The researchers came up with a range rather than a single number, and estimated that 800–2,300 inmates were incarcerated for possession alone without any evidence of involvement in distribution. Even their highest estimate—2,300 individuals in prison just for marijuana use—would still only be two-tenths of 1 percent of the prison population.

These figures should surprise no one. Police tell us they actively pursue drug sellers, but not drug users, and that’s what the prison statistics show. These numbers are so low the researchers concluded that “marijuana decriminalization would have almost no impact on prison populations…”22

It takes a special effort to get incarcerated for marijuana

Legalization advocates say that any marijuana user could be arrested and imprisoned. However, about 20 million Americans used marijuana in 199724 whereas only about 400 were in prison solely for possession. Were these 400 incarcerated at random, or did they do something unique?

Oklahoma has some of the toughest marijuana laws in the nation, yet defense attorneys interviewed for an article in The Oklahoman agreed that people arrested for marijuana possession mostly get treatment or probation. One prosecutor said, “You have to work very hard to go to prison on drug possession cases in Oklahoma.25

This is true everywhere, especially for marijuana. Police aren’t out looking for marijuana users, so when anyone says they’re incarcerated only for possession we should ask how they were caught. There’s always more to the story. I’ve spoken with four inmates or former inmates who told me they were in prison only for marijuana possession. Here’s what I learned about them:

- One was pulling a rental truck filled with the drug.

- The second was actually arrested for robbery, but was searched and marijuana was found. He said the store he robbed refused to press charges—they apparently didn’t want the publicity–so the judge threw the book at him for the marijuana.

- The third was on probation when the police pulled him over and found marijuana in his glove box. I asked why they pulled him over, and he said he was driving without a license. So I asked how the police knew this, and it was because they had pulled him over the day before. In other words, he was on probation and had just been caught driving without a license, and then the next day he drove again anyway and carried an illegal drug. This is not just bad judgment, but a pattern of violating the law.

- The fourth really was in prison only for marijuana. He smoked marijuana outdoors, insisting it was his right. But his neighbors didn’t want their children seeing drug use, so they called the police—repeatedly. After this man’s ninth arrest, the judge made him serve some time. His story illustrates that it’s not easy to get incarcerated just for marijuana. It takes real persistence.

Research shows that incarceration for simple possession is rare, but marijuana advocates want us to believe that it’s common and could happen to anyone.

In a 2015 effort to convince Congress to legalize medical marijuana nationally, Senator Rand Paul (R-Kentucky) stood with several medical marijuana users and said, “If one of these patients up here takes marijuana in the states where it’s illegal, they will go to jail.”26 That is not true. But the campaign for legalization depends on convincing us that jails and prisons are filled with otherwise innocent marijuana users. So to sway public opinion, advocates like Senator Paul make claims that research long ago proved to be false.

In a September 2014 interview, pro-legalization billionaire Richard Branson said, “If my children had a drug problem, I’d want them to be helped, not sent to prison.”27 That’s already what happens today. Branson implied that anyone caught possessing drugs risks being sent to prison, but that’s not the case. If his children were caught with drugs, they would probably get help. Judges want addicts in treatment, not jail. So the average person who uses marijuana or any other illegal drug is at virtually no risk of going to prison for possession.

.

.

3. Police do not pursue individual drug users

As people learned that prisons are not full of innocent drug users, the marijuana lobby changed tactics and started complaining about the number of people arrested. The DPA website says, “Marijuana arrests are the engine driving the U.S. war on drugs. Nearly half of all drug arrests each year are for marijuana-related offenses, the overwhelming majority of which are for personal possession.”28

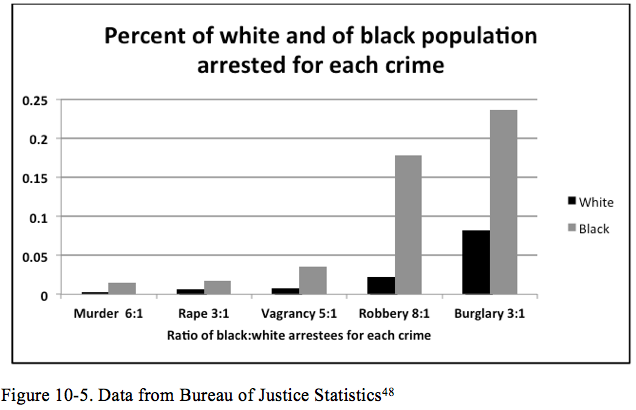

They are correct about one thing: the arrests are real. In 2009, the United States had more than 13 million arrests. Twelve percent, just over 1.5 million, were for drug crimes. And nearly 80 percent of those were for possession. Based on data from prior years, approximately 42 percent of the drug possession arrests were for marijuana.29

The arrest picture is almost the opposite of the incarceration picture: 90 percent of those in prison for drug crimes are traffickers and barely anyone is there for possession; whereas 80 percent of drug arrests are for possession. And while the incarceration rate for marijuana possession is minuscule, arrests for marijuana possession make up nearly half of all drug crime arrests.

This raises two questions:

- We apparently don’t think drug possession is a crime deserving of incarceration, so why are so many people arrested for it?

- Do all these arrests for possession represent drug policy gone mad, as the marijuana lobby claims, or is there another explanation?

There is a much more likely explanation: For the most part, police aren’t looking for drug users; they find them unintentionally. Most arrests for possession happen incidentally when someone is searched after they’re stopped or arrested for an entirely different reason. The real cause of the high arrest rate for possession is the high rate of drug abuse among criminals, and the tendency of drug abusers to always carry their drugs with them.

Who commits crime?

In the developed world, crime is mostly a symptom of substance abuse. According to Behind Bars, a report by the Center for Addiction and Substance Abuse, nearly two-thirds of all jail and prison inmates meet criteria for the diagnosis of substance abuse. This is seven times the rate of substance abuse found in the general population, which, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, is 8.7 percent of everyone over age eleven.32

There’s also research showing how many criminals used drugs shortly before being arrested. The Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring survey (ADAM) does annual drug screens on a sample of those arrested for all types of crime in five major cities. In 2012, the percentage testing positive for any illicit drug ranged from 62 percent in Atlanta to 86 percent in Chicago. The average across the five cities was 75 percent. The most commonly used drug was marijuana, ranging from 37 percent of those screened in Atlanta to 58 percent in Chicago. The average was 49 percent.33

I work with substance abusers. The patients I treat get high several times a day and carry their drugs everywhere. They never want to be far from their supply. They even carry drugs when committing a crime. First of all, most crime is spontaneous, not pre-meditated, and often committed by people who are under the influence. But even when it’s planned out, getting caught is never part of their calculation, while getting high is.

According to the ADAM survey, at least three-quarters of all criminals use illegal drugs. If they carry their drugs at all times, they’ll get arrested for drugs as well as for the crime they were caught committing.

This is the most likely explanation for the half million marijuana arrests every year. There are exceptions, of course. There are stories of police asking people if they’re carrying marijuana, and then arresting them when they show it. But in most cases, police aren’t out to find marijuana; it finds them.

Evidence that more criminals are carrying marijuana

On November 12, 2012, the Vancouver Sun ran an article with the headline, “Pot possession charges in B.C. up 88 per cent over last decade.” According to the article, there were 3,774 marijuana possession charges in 2011. It also included quotes from three legalization advocates who painted a picture of police actively pursuing marijuana users.34

One quote was from a criminology professor who said, “It’s a police-driven agenda …”35

Another quote was from the former editor of Cannabis Culture magazine, who said he was working on a referendum to prevent police from “searching, seizing or arresting anyone for simple cannabis possession.”36 That makes it sound like police are intentionally pursuing people whose only crime is marijuana possession.

The Sun also quoted the executive director of the pro-legalization Beyond Prohibition Foundation, who asked, “What are we doing continuing to waste very scarce and shrinking prosecutorial and judicial resources going after marijuana offenders?”37 No one opposed to legalization was quoted, but there is another side to the story — a side to the story the Vancouver Sun did not tell.

Kale Pauls, an officer with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), says they’re misinterpreting the data. According to his master’s thesis and a report he co-wrote for the Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research, barely anyone is charged for marijuana possession in British Columbia.38 That would mean police are not actively pursuing marijuana offenders and the province is not wasting resources.

Here’s how the data is misinterpreted: In British Columbia, each time someone is stopped or arrested for any crime, police are required to create a file for this one incident. The file includes every crime the person committed as part of this incident, whether they’re charged for that crime or not. Police are also required to record how the file was disposed of, or cleared. If the person is charged with a crime, the case is recorded as “cleared by charge.” If the person gets a warning but no charges, the file is recorded as “cleared by other means.”

But there’s a strange quirk in the rules. If the person is charged for one crime in an incident, the entire file and all of the offences contained in that file are listed as “cleared by charge.” If someone is arrested and charged with a crime, and the police also confiscate marijuana but don’t lay any charges for it, the marijuana possession would still be listed as part of the incident file that is “cleared by charge.” So if the police arrest someone for burglary and find marijuana on the person when they are searched, the offender might only be charged with burglary. But because of the way in which police are required to report the data, Statistics Canada will also record the marijuana possession as “cleared by charge.”

That’s right: “marijuana possession, cleared by charge” doesn’t mean the person was charged with marijuana possession. It’s confusing, so it’s hard to blame the Vancouver Sun for misreading the data. Still, their article, including the headline, got it wrong.

Here’s the evidence: According to Pauls, in 94 percent of the cases recorded as marijuana possession cleared by charge, the person was also charged with another crime. When marijuana possession was the only crime, 96 percent of those cases were cleared “otherwise,” which means the person was not charged with any offence. Those are often the cases that got only a warning.

In other words, when marijuana was the only crime, the individual was almost never charged with any offence. When someone was charged with an offence and marijuana was present, they were almost always charged for the other crime, and not for marijuana possession. In other words, almost no one was charged with marijuana possession.39

I say “almost no one” because in 249 of the cases in which marijuana possession was the only crime, the suspect was charged. But in the other 93 percent of cases that the Vancouver Sun called marijuana charges there were probably no marijuana charges at all.40

So why were 249 people charged with marijuana possession? According to retired RCMP officer Chuck Doucette, the most common reason for a stand-alone possession charge is that someone suspected of selling drugs was caught with drugs but without enough evidence to corroborate a charge of possession for the purpose of trafficking. Another common scenario is police responding to domestic violence but the spouse, often out of fear, changes her mind and decides not to prosecute. Police don’t want to leave her alone with someone who was just abusing her, but they need an excuse to take him away. If they can find drugs, and they usually can, then they can get the abuser out of the home. Those two scenarios could account for all the times someone is charged solely for marijuana possession.

What happened to those 249 people charged with marijuana possession alone is also telling. Only forty-two were convicted, and of those, only seven served any time—four served one day in jail, two served one week, and one served two weeks.41

So the Vancouver Sun article was very misleading. It overstated the number of people charged with marijuana possession and then quoted three pro-marijuana activists who gave the impression that police are deliberately pursuing otherwise innocent marijuana users.

What the statistics actually show is that police almost never lay charges against otherwise innocent marijuana users. Those people almost always get warnings. (And we might not need the word “almost.”)

The term for this type of restraint is de facto decriminalization; the laws are still on the books, but they’re not enforced. And that means marijuana possession is already effectively decriminalized in British Columbia.

* * *

I speculated that the arrest rate for marijuana possession is sky-high in the United States because substance abusers, who make up the majority of all criminals, carry their drugs with them. In British Columbia, this is not speculation. The numbers reported in the Vancouver Sun show that B.C. police often find marijuana on people who get arrested for other reasons. In fact, the statistics show that over the ten years ending in 2012, the number of criminals carrying marijuana at the time of arrest increased by 88 percent.

The best explanation for the huge number of marijuana arrests throughout the rest of Canada and in the United States is the same: An increasing number of criminals use marijuana and carry it with them at all times, even when they commit crimes. The marijuana is found incidentally when people are stopped or arrested for different reasons. Police don’t actively pursue the drug; it comes to them.

Legalization won’t free up police time

There’s a “War Against Marijuana Consumers,” the NORML website says, that “places great emphasis on arresting people for smoking marijuana.”42 The ACLU says police nationwide have made the “War on Marijuana” a priority, and waste billions of taxpayer dollars on the “aggressive enforcement of marijuana possession laws.”43 It might sound like a dangerous time for drug users. However, there is no such war.

Police are not interested in marijuana. They don’t dress in plain clothes at rock concerts to nab people who light up. They don’t patrol university dorms with drug-sniffing dogs. There are no big sweeps to round up marijuana users. They don’t even make arrests at some of the public marijuana protests.44

Big city police departments have special units to investigate homicide, fraud, child abuse, auto theft, stolen property, and many other major crimes, but there is no special unit to investigate marijuana possession. Police don’t go undercover to flush it out and don’t keep lists of suspects who might be using the drug.

They don’t even pursue leads. Police never say, “We got word this person is smoking marijuana; let’s stake the place out and see.” Call them with a tip about stolen property, and they’ll take you seriously. Call about your neighbor who gets high inside his own home, and they’ll treat you like a crank.

The war on marijuana is a fiction, but a useful one. It was used to convince voters that legalization would free up police to pursue serious crimes. But police don’t spend time or money looking for marijuana users, so there’s nothing to free up.

Police departments don’t want to say they’re not enforcing the law, so they say marijuana possession is not a priority. It means they don’t go looking for it, but they often find it while investigating other offences that are a priority.

The pot lobby wants the public to believe that marijuana arrests and the pursuit of serious crime are separate entities and that police can choose one or the other. Ironically, possession arrests only seem to happen when police are pursuing other crime.

Exploiting the oppressed

As part of its pro-legalization campaign, the marijuana lobby highlighted two groups of people who are seriously mistreated by the U.S. criminal justice system. One group is the million or so Americans in prison who probably would not have been incarcerated before the Reagan-era “tough on crime” legislation. The other is people of color, especially African-Americans.

The marijuana lobby has successfully drawn attention to the unequal treatment these two groups have received, and that’s good. However, legalizing marijuana would not help either group. And focusing on legalization distracts attention from the real source of the injustices.

Legalizing drugs would free the wrong people from prison

I’ve worked in several jails and prisons and met many inmates. Some seemed like they shouldn’t have been there at all, and many had sentences that seemed far too long for what they’d done. I’ve also met inmates with schizophrenia, locked up for obeying the voices they hear, who told me the only time they got medicine for their hallucinations was in prison. I’ve met inmates with severe head injuries, PTSD, and other psychiatric problems who never got treatment on the outside. Most of all, I’ve met men and women with drug and alcohol problems who had never received treatment and claimed it had never been offered or suggested.

The majority of people in prison have treatable problems, and treatment could keep them from coming back over and over. Many of them have received unfairly long sentences. Quite a few are veterans who fought for their country, yet never got the help that would have kept them out of trouble. But most of these people aren’t in prison for drug crimes so legalizing drugs would not help them at all.

Legalization would not free any of the people whose sentences for violent and property crimes are too long, and it would not give people with psychiatric illness or substance abuse the treatment they need to avoid returning to prison.

Instead, legalizing drugs would free the inmates with whom I sympathized the least: dealers who sold drugs they didn’t use themselves. These inmates knew how deadly crystal meth and heroin could be, and didn’t care. It was just easy money. No untreated disease got them to commit crimes. They weren’t drunk, high, or hearing voices. Drug dealers are in prison because their greed overrode their humanity.

Nearly 90 percent of people in state prison for drug crimes are in for trafficking. In federal prison, it’s nearly 100 percent. Drug legalization advocates would come to the aid of these drug dealers while ignoring hundreds of thousands who, in my opinion, really are locked up unfairly.

By implying that high incarceration rates are mainly caused by drug arrests, the marijuana lobby is distracting attention from the real cause of prison overcrowding. And by claiming the solution is legalization, they’re distracting us from the real cure.

Minorities and marijuana

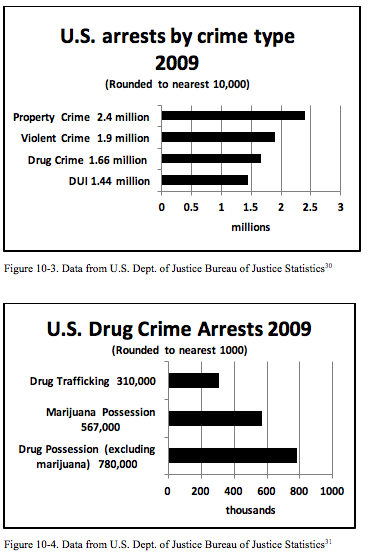

In June 2013, the ACLU released a study showing black Americans are nearly four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as whites, even though both races smoke marijuana at the same rate. The exact figure was 3.73 times more likely.45

According to the ACLU, America’s police have carried out a “War on Marijuana” with “staggering racial bias.”46 From the news reports, it sounded like police were intentionally rounding up African-American marijuana users.

However, the most likely explanation for marijuana arrests is that police find the drug incidentally while searching someone who’s been arrested or stopped for an entirely different reason. So, if blacks are arrested for marijuana possession at four times the rate of whites, it’s probably because they are stopped, searched, and arrested for reasons unrelated to marijuana at four times the rate of whites. And they are.47

African-Americans are arrested for almost all crimes at much higher rates than whites, and it has nothing to do with marijuana. African-Americans are arrested for violent crime at 3.9 times the rate of whites and for property crime at 2.6 times the rate. African-Americans are 2.8 times more likely than whites to be arrested for rape or burglary, 4.5 times more likely to be arrested for vagrancy, 5.9 times as likely to be arrested for murder, and 7.7 times more likely to be arrested for robbery. They’re also stopped and searched much more frequently, even when there is no arrest.49

I’m not saying this is fair because it’s definitely not. According to biological research, race is an imaginary distinction man made up based on a handful of superficial characteristics. From a scientific perspective, race is impossible to define and doesn’t even exist.50 We should probably use the terms “so-called white people” and “so-called black people” to free ourselves from this invalid notion of race.

So while the statistics tell us African-Americans commit proportionally more crime, this can’t be attributed to racial differences because there are none. The high arrest rate for African-Americans for all crimes is due to something wrong with our criminal justice system or something wrong with our culture—or both. And we know it’s both. Racial profiling is real, and so is the United States’ long history of discrimination. Many of the theories that seek to explain the higher crime rate among African-Americans point to persistent prejudice and mistreatment.51 The legalization lobby wants to make marijuana laws the villain in this story, but the real culprit is racism.

However, that didn’t stop newspapers across the United States from using the ACLU study as a slam on marijuana laws. It didn’t stop the New York Times from writing a headline that started with “Blacks Are Singled Out for Marijuana Arrests,” and then failing to mention the high black arrest rate for all crimes.52 It didn’t stop E.J. Dionne, of the Washington Post, from writing that marijuana should be legalized because it’s unfair that blacks are arrested for possession at such high rates.53 And it didn’t stop the New York Times or Washington Post from using the articles to discuss legalization—even though no one suggests we legalize robbery or any other crime for which blacks are disproportionately arrested.54 The ACLU and the press took a huge racial injustice and used it, not to aid those suffering from discrimination, but to promote legalization.

I am not defending the police. There is plenty of police harassment directed toward African-Americans. What I’m saying is that African-Americans are not singled out for marijuana; they’re singled out for being black.55 Drug laws are not the problem; the problem is racism.

Besides, legalizing marijuana would not help the African-American community. The drug is just as harmful for black teenagers as for whites, and it interferes with education and employment for African-Americans as much as for anyone else. The alcohol and tobacco industries already target black neighborhoods with advertising; a legal marijuana industry would only exploit them more. The marijuana lobby is using the plight of African-Americans to promote legalization, but legalization would make their plight worse.

Incidentally, what’s not in the news coverage is the $7 million pro-marijuana billionaire Peter Lewis gave to the ACLU,56 or the $50 million George Soros gave them more recently. If a group took money from the oil or coal industry and came out with a study questioning global warming, that funding would be part of every news report and the research would be discredited. But for marijuana, the press ignored this conflict of interest.

More evidence of media bias

The same week the ACLU released its report, the University of Maryland also released a study on marijuana. According to USA Today, this ten-year research project found that university students who used marijuana studied less, skipped more classes, earned lower grades, dropped out at higher rates, and were more likely to be unemployed later in life. “Even infrequent users—those who smoked about twice a month”—had more problems in school than nonusers.57

The quality of this research was very good, and the subject—the education of our youth—is certainly serious. But when I did a Google news search in June 2013, the ACLU story showed up in 193 news sources while the University of Maryland study showed up in one.58

Given a choice between a research study critical of marijuana and one that supports the drive for looser laws, the U.S. news media decided overwhelmingly to promote legalization.

Chapter 10 Endnotes

1. The PIPA/Knowledge Networks Poll (Oct. 2, 2003) “Misperceptions, The Media And The Iraq War” Principal Investigator Steven Krull www.pipa.org/OnlineReports/Iraq/IraqMedia_Oct03/IraqMedia_Oct03_rpt.pdf

Gallup (2014) ”Foreign Affairs: Iraq” www.gallup.com/poll/1633/iraq.aspx

2. Tilem & Associates “The Richard Nixon Era – The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 Eliminates Mandatory Minimums” (Jan. 19, 2009) New York Criminal Attorney Blog www.newyorkcriminalattorneyblog.com/2009/01/the_richard_nixon_era_the_comp.html

Keith Humphreys “Who started the war on drugs?” (June 1, 2011) The Reality-Based Community www.samefacts.com/2011/06/drug-policy/who-started-the-war-on-drugs/

3. Richard Nixon “Special message to Congress on drug abuse prevention and control” (June 17, 1971) The American Presidency Project www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=3048

4. Michael Massing “The Fix” University of California Press 2000 www.amazon.com/The-Fix-Michæl-Massing/dp/0520223357

5. Ibid.

6. The Pew Center on the States (June 2012) “Time Served: The High Cost, Low Returns of Longer Prison Terms” www.pewstates.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2012/Pew_Time_Served_report.pdf

“Timeline: The Evolution Of California’s Three Strikes Law” NPR (Oct 28, 2009) npr.org http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=114250301

7. National Center for Policy Analysis (Jan. 13, 1999) “States Are Abolishing Parole” www.ncpa.org/sub/dpd/index.php?Article_ID=12601

Families Against Mandatory Minimums (Sept. 21, 2013) “Frequently asked questions about the lack of parole for federal prisoners” http://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FAQ-Federal-Parole-11.29.pdf

Families Against Mandatory Minimums (Feb. 25, 2013) “Federal Mandatory Minimums” http://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Chart-All-Fed-MMs-NW.pdf

Families Against Mandatory Minimums (June 30, 2013) “Recent State-Level Reforms To Mandatory Minimum Laws” http://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FS-List-of-State-Reforms-6.30.pdf

“Excerpt from Introduction to Federal Sentencing Guidelines” http://www1.law.umkc.edu/suni/CrimLaw/fed_sent_guide.htm

8. Michael Massing “The Fix” University of California Press 2000 www.amazon.com/The-Fix-Michæl-Massing/dp/0520223357

9. From “US Incarceration Timeline” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Jan. 24, 2012. Original by the November Coalition. http://november.org/graphs/ Modified by Sarefo July 28, 2009 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US_incarceration_timeline-clean.svg Sources: Justice Policy Institute Report: The Punishing Decade & U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin NCJ 219416 – Prisoners in 2006. Modified by changing from color to black & white. Original and modifications licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US_incarceration_timeline-clean-fixed-timescale.svg http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US_incarceration_timeline-clean.svg The edited version here is available for use and licensed under the same Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode.

10. Ibid.

11. The Pew Center on the States (June 2012) “Time Served: The High Cost, Low Returns of Longer Prison Terms” www.cdcr.ca.gov/realignment/docs/Report-Prison_Time_Served.pdf

12. Michael Massing “The Fix” University of California Press 2000 www.amazon.com/The-Fix-Michael-Massing/dp/0520223357

13. Keith Humphreys “Who started the war on drugs?” (June 1, 2011) The Reality-Based Community www.samefacts.com/2011/06/drug-policy/who-started-the-war-on-drugs/

14. Drug Policy Alliance (July 21, 2014) “The Drug War, Mass Incarceration and Race” www.drugpolicy.org/resource/drug-war-mass-incarceration-and-race

15. American Civil Liberties Union (Jan. 1, 2015) “Smart Justice, Fair Justice” https://www.aclu.org/feature/smart-justice-fair-justice?redirect=smart-justice-fair-justice-0%2Csmart-justice-fair-justice

16. Marijuana Policy Project (Jan. 1, 2015) “Like it or not, we can’t afford marijuana prohibition” www.mpp.org/media/op-eds/like-it-or-not-we-cant-1.html

17. Howard N. Snyder, PhD (Sept. 2011) “Arrest in the United States 1980-2009” U.S. Department of Justice http://gb1.ojp.usdoj.gov/search?q=cache:gYDYmR1XIl4J:www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf+aus8009.&site=BJS-OJP&client=bjsnew_frontend&proxystylesheet=bjsnew_frontend&output=xml_no_dtd&ie=UTF-8&access=p&oe=UTF-8

18. Rick Perlstein Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (May 2008) Scribner http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/05/e-pluribus-nixon/306765/

- NORML (Nov. 21, 2007) “Decriminalizing pot will reduce prison population, have no adverse impact on public safety, study says” (Press release) http://norml.org/news/2007/11/21/decriminalizing-pot-will-reduce-prison-population-have-no-adverse-impact-on-public-safety-study-says

- Katrina vanden Heuvel “Time to end the war on drugs” (Nov. 20, 2012) The Washington Post www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/katrina-vanden-heuvel-time-to-end-the-war-on-drugs/2012/11/19/2ef5099e-326e-11e2-9cfa-e41bac906cc9_story.html

- Institute for Behavior and Health (July 31, 2009) “How Many People Does The U.S. Imprison For Drug Use And Who Are They?” Jonathan P. Caulkins and Eric L. Sevigny http://ibhinc.org/pdfs/CaulkinsSevignyHowanydoestheUSimprison2005.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012. www.samhsa.gov/data/nhsda/pe1997/popes105.htm#E10E19

- Juliana Keeping “Oklahoma’s harsh marijuana possession law has its critics” (Feb. 2, 2014) The Oklahoman http://newsok.com/oklahomas-harsh-marijuana-possession-law-has-its-critics/article/3929861

- “Senate’s old guard just says ‘no’ to pot overhaul” (March 24, 2015) Politico http://www.politico.com/story/2015/03/senates-old-guard-just-says-no-to-pot-overhaul-116336.html#ixzz3Vdg60Ef3

- 27. “Richard Branson: ‘The Virgin Way’” (Sept. 23, 2014) The Diane Rehm Show WAMU http://thedianerehmshow.org/shows/2014-09-23/richard-branson-virgin-way

- Drug Policy Alliance (Dec. 30, 2014) “Reducing the Harms of Marijuana Prohibition” www.drugpolicy.org/reducing-harms-marijuana-prohibition

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (Sept. 2011) “Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009” Howard N. Snyder, PhD www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (Jan. 1, 2015) “Drug and Crime Facts” www.bjs.gov/content/dcf/enforce.cfm

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (Sept. 2011) “Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009” Howard N. Snyder, PhD www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf

- The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (Feb. 2010) “Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population” www.casacolumbia.org/addiction-research/reports/substance-abuse-prison-system-2010

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012. http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.htm#7.1

- Office of National Drug Control Policy Executive Office of the President (May 2013) “Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II 2012 Annual Report” www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/adam_ii_2012_annual_rpt_final_final.pdf

- Zoe McKnight “Pot possession charges in B.C. up 88 percent over last decade: Poll suggests three-quarters of population would rather tax and regulate marijuana” (Nov. 4, 2012) The Vancouver Sun www.vancouversun.com/news/possession+charges+cent+over+last+decade/7492120/story.html

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kale Pauls. “The nature and extent of marihuana possession in British Columbia; A report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts in criminal justice in the school of criminology and criminal justice” (Spring 2013) University of the Fraser Valley.

- Kale Pauls, Darryl Plecas, Irwin M. Cohen & Tara Haarhoff. “The nature and extent of marihuana possession in British Columbia” (Nov. 24, 2013) Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research http://cjr.ufv.ca/the-nature-and-extent-of-marihuana-possession-in-british-columbia/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- NORML (Jan. 1, 2015) “War Against Marijuana Consumers” http://norml.org/legal/item/war-against-marijuana-consumers

- American Civil Liberties Union (Jan. 1, 2015) “The War On Marijuana In Black And White: Billions of dollars wasted on racially biased arrests” https://www.aclu.org/billions-dollars-wasted-racially-biased-arrests

- Vancouver Sun – Editorial. (Sept. 12, 2013). www.vancouversun.com/news/problem+only+society+decides+make/8907798/story.html

- American Civil Liberties Union (Jan. 1, 2015) “The War On Marijuana In Black And White: Billions of dollars wasted on racially biased arrests” https://www.aclu.org/report/war-marijuana-black-and-white?redirect=criminal-law-reform/war-marijuana-black-and-white%2Ccriminal-law-reform/war-marijuana-black-and-white-report

- American Civil Liberties Union (Jan. 1, 2015) “The War On Marijuana In Black And White: Billions of dollars wasted on racially biased arrests” https://www.aclu.org/billions-dollars-wasted-racially-biased-arrests

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (Sept. 2011) “Arrest in the United States, 1980-2009” Howard N. Snyder, PhD www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf

- Ibid. www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf

- Ibid.http://gb1.ojp.usdoj.gov/search?q=cache:gYDYmR1XIl4J:www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus8009.pdf+aus8009.&site=BJS-OJP&client=bjsnew_frontend&proxystylesheet=bjsnew_frontend&output=xml_no_dtd&ie=UTF-8&access=p&oe=UTF-8

- BlackDemographics.com (2012) “African Americans & Crime” http://blackdemographics.com/culture/crime/

- Alan R. Templeton (Sept. 1998) “Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective” American Anthropologist http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.632/abstract

- “Interview with Richard Lewontin” (2003) PBS www.pbs.org/race/000_About/002_04-background-01-04.htm

- Tony Fitzpatrick (Feb. 9, 2010) “Biological differences among races do not exist, WU research finds” Washington University in St. Louis wupa.wustl.edu/record_archive/1998/10-15-98/articles/races.html

- Helen Taylor Greene & Shaun L. Gabbidon Race and Crime (2012) SAGE Publications http://www.sagepub.com/upm-data/40397_3.pdf

- Ian Urbina “Blacks are singled out for marijuana arrests, federal data suggests” (June 3, 2013) The New York Times www.nytimes.com/2013/06/04/us/marijuana-arrests-four-times-as-likely-for-blacks.html?_r=1&

- E.J. Dionne, Jr. “Opinion: Marijuana Injustices” (Jan. 8, 2014) The Washington Post www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/ej-dionne-marijuana-injustices/2014/01/08/3402d55c-78a3-11e3-8963-b4b654bcc9b2_story.html?hpid=z2

- Annys Shin “D.C. Marijuana Study: Blacks far more likely to be arrested than whites, ACLU says” (June 4, 2013) The Washington Post www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-marijuana-study-blacks-far-more-likely-to-be-arrested-than-whites-aclu-says/2013/06/04/fa0d83d2-cd40-11e2-8f6b-67f40e176f03_story.html

- “Cops see it differently, Part Two” (Feb 13, 2015) This American Life, WBEZ http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/548/cops-see-it-differently-part-two)

- American Civil Liberties Union (July 18, 2001) “Individual donor sets record with $7 million donation, largest-ever endowment gift to ACLU” (New release) https://www.aclu.org/free-speech/individual-donor-sets-record-7-million-donation- largest-ever-endowment-gift-aclu

- Amelia Arria, PhD et al. “The Academic Opportunity Costs of Substance Abuse During College” (May 2013) Center on Young Adult Health and Development www.cls.umd.edu/docs/AcadOppCosts.pdf

- David Schick “Study: Marijuana use increases risk of academic problems” (June 7, 2013) USA Today www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/06/07/marijuana-academic-problems/2399693/

- June 2013 Google news search

.

.

.

.

.

Chapter 23: What Legalization Would Unleash

The drive to legalize marijuana should be seen in context—the marijuana lobby’s overarching goal is to decriminalize or legalize all currently illegal drugs. The Global Commission on Drug Policy has already called for all countries to decriminalize all drug possession and to “regulate drug markets.”1 Remember, they believe that only a legal drug can be regulated, so when they use the term regulate, they mean legalize.

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition issued a report calling for “the decriminalization of all drugs for personal use.”2 The Drug Policy Alliance’s mission statement says it “envisions a … society in which … punitive prohibitions of today are no more.”3 That certainly sounds like legalizing all drugs.

The DPA’s director of media relations made that explicit in a blog post by writing, “My colleagues and I at the Drug Policy Alliance are committed to ensuring the decriminalization of all drug use …”4 This movement believes people should have the legal right to obtain and use any drug.

The three groups just named are all funded by George Soros and his Open Society Foundations or Institute. Legalization or decriminalization of all drugs has apparently always been their aim; now they’re saying it openly, and so are many opinion writers.

For example, Conor Friedersdorf of the Atlantic wrote an article titled “America Has a Black Market Problem, Not a Drug Problem.” In it, he blames drug laws for gang violence and describes the benefits, as he sees them, of legalizing all drugs.5

The Economist has called for legalizing all drugs. Eugene Robinson of the Washington Post blamed the heroin overdose death of actor Phillip Seymour Hoffman on drug laws, saying that when drugs are black market commodities, it’s impossible for addicts to know what they’re injecting.6 It’s an erroneous argument, however, because the abuse of prescription opiates kills far more people than heroin, and addicts know exactly what manufactured pharmaceuticals contain.

Libertarians are also very open about their aim. Not all libertarians are pro-legalization, but many are. The libertarian Cato Institute and other strongly ideological libertarian organizations support the legalization of all drugs.7

So the legalization of marijuana should be seen in the context of what would certainly come next: a push to decriminalize or legalize all drugs of abuse. The movement is already laying the groundwork and painting a rosy picture of universal legalization.

But to paint this rosy picture, they ignore all the costs and all the problems legalizing drugs would cause. For example, the Cato Institute published a report estimating that the United States would reap $88 billion in savings and tax revenue from legalizing all drugs, but never mentioned a single cost.8 That’s like computing all the gas money you’d save by selling your car without ever considering what you’d spend to get around without one.

The social and economic cost of legalizing all drugs would be substantial. In fact, they’d be staggering. It’s hard to grasp all the suffering this would unleash. Substance abuse plays a role in every social problem we have, and a major role in the most serious ones.

One of the most serious is child abuse, which has extra significance because it’s also a cause of nearly every social problem. As we will see in the rest of this chapter, child abuse and substance abuse together cause much of the world’s grief. However, adults with alcohol and other drug problems are responsible for most of the child abuse, so substance abuse is still the primary problem that leads to all the others. That should be our main consideration when we contemplate legalizing drugs.

Pandora’s bag and bottle:

Twenty-one ways legalization would harm us all

Here’s a list of twenty-one problems that plague modern society. Substance abuse and child abuse are on the list, but they are also the causes of every problem on the list.

Only crime, domestic abuse, and child abuse involve violence, but all twenty-one problems drag us down economically and emotionally. This is what the legalization lobby doesn’t tell us. These twenty-one problems affect us all, and they will grow in size and severity if we legalize all drugs. Here is some of the evidence the substance abuse and child abuse are, at least partially, causes of all twenty-one problems:

Crime

Two-thirds of prison inmates are substance abusers.9 Three-quarters of arrestees test positive for drugs.10Most crime—including most property and violent crime—is a symptom of substance abuse.11 Legalization would increase drug use, which would increase crime. Research also shows that people who were abused or neglected as children are nine times as likely to break the law as adults, and were more likely to be serving time for a violent crime than inmates who were not abuse victims.12 So child abuse also increases crime. Two aspects of crime deserve special mention:

Prison overcrowding. Nearly 80 percent of U.S. prison inmates are incarcerated for crimes that are not drug-related, but even these non-drug crimes are mostly caused by substance abuse. So these crimes would increase with drug legalization, and the net result would be more crime and more people in prison.

Gangs. Gang members use drugs and alcohol at high rates, and are responsible for most crime in the U.S., including armed robbery, identity theft, and weapons trafficking.13 Factors that predispose teenagers to join gangs include substance abuse, serious problems at home (often involving substance abuse), and neighborhoods with lots of drug use.14 More drugs would mean more gang members.

Child abuse

According to CASA Columbia, “70% of abused and neglected children have alcohol or drug abusing parents.”15 Child abuse is primarily a symptom of substance abuse, so it would increase with legalization.

Domestic violence

Substance abuse precipitates violence in violence-prone people so regularly that it’s an ingredient in the majority of domestic violence cases.16 A 1995 study found that 92 percent of perpetrators had used drugs or alcohol the day of the assault.17 Legalization of all drugs would mean more domestic violence.

Drug and alcohol abuse

Drug and alcohol abuse cost the United States over a $400 billion per year, most of it in lost productivity.18Substance abuse would certainly increase with legalization.

Drunk and drugged driving

Drunk driving fatalities have declined since Mothers Against Drunk Driving was founded in 1980. But drugged driving and combined drug-and alcohol-impaired driving have increased. The number of traffic fatalities caused by drugged driving has increased with greater availability of marijuana, and would increase even more with legalization.

Homelessness

According to research cited in Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill, about two-thirds of the chronically homeless are substance abusers.19 However, substance abuse by itself does not lead to homelessness. A study of homeless adults found that nearly half had been so severely abused as children they were removed from their homes by CPS.20 At Healthcare for the Homeless in central Phoenix, where I worked, severe childhood abuse was also a part of nearly every patient’s story.

Welfare dependency

Only 15–20 percent of people on welfare have substance abuse disorders, but they stay on welfare the longest.21

High healthcare costs

Adults who were abused as children have more surgeries and more medical and psychiatric problems.22Substance abusers run up healthcare bills for a host of medical problems that often require hospital stays, emergency room visits and addiction treatment.

Teen pregnancy

Women who were sexually abused are three times as likely to get pregnant in their teens.23 Abused boys are more likely to father a teen pregnancy.24 And substance abusers are notorious for indulging in promiscuity and risky sexual behavior. According to Joseph Califano, former Health, Education, and Welfare secretary, “Most unplanned teenage pregnancy occurs when one or both parties are high at the time of conception.”25

Abortion and unwanted pregnancy

Research shows that substance abusers have higher rates of abortion than nonusers.26 One study showed 5 percent of abortions occurred because women were afraid they’d harmed the fetus with drugs or alcohol, or that substance use would make them or their partner an unfit parent.27 A study done at California State University in 1993 found that childhood sexual abuse was related to an increased likelihood of a woman having an abortion.28 So preventing substance abuse would lower the abortion rate whereas legalizing drugs would increase it.

AIDS

About 40 percent of new HIV cases involve intravenous drug users or their heterosexual partners. But even among gay men with HIV, most have used illegal drugs.29 The reason is that substance abusers of all sexual orientations are more likely to have unprotected sex and multiple partners—and those behaviors put them at risk of AIDS.30

Prostitution

Street prostitutes almost always have a history of substance abuse.31 The prostitutes we treated at Healthcare for the Homeless all used the money to pay for drugs. But childhood sexual abuse is also part of the story. In The Sexualization of Childhood, edited by Sharna Olfman, prostitution researcher Melissa Farley calls sexual abuse of children the “training ground for prostitution.” She describes research showing that sexually abused girls are twenty-eight times as likely to engage in prostitution, and another study that found 82 percent of prostitutes in Vancouver, B.C., were sexually abused as children.32

Poverty

Substance abuse drags people into poverty three ways. Addicts and alcoholics find it much harder to hold onto a job. They spend their money on drugs and alcohol. And they develop health problems that drain their savings and make it harder to work.

Chronic unemployment

The unemployed have twice the rate of substance abuse as the general population.33 And usually it’s substance abuse that leads to poverty and unemployment, not the other way around. A review of the research published in 2011 showed that drug and alcohol abusers had more difficulty finding employment and were more likely to lose jobs they had.34

High school dropouts

Students who use marijuana regularly before age sixteen drop out twice as often as nonusers.35 A study published in the Lancet found that even occasional marijuana users have an increased dropout rate.36 And marijuana is not the only cause; teens who abuse alcohol or other illegal drugs also drop out at higher rates.37

Divorce

Research on divorce found substance abuse to be the third most common reason, after infidelity and incompatibility.38

Single moms

Families headed by a single mom are five times as likely to be poor as families headed by a married couple.39Two of the most common causes of single parenthood are divorce and unwanted pregnancy, both of which are often caused by substance abuse.

Deadbeat dads

Research shows that one-quarter of all parents who are owed child support receive nothing. And state programs that pursue parents who don’t pay child support often find the problem is substance abuse.40

Grandparents raising grandkids

The 2000 U.S. census found that over 2.4 million grandparents were raising their grandchildren.41 Families headed by a grandparent often have financial problems. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, common reasons for biological parents leaving their kids with grandparents are substance abuse and several problems that are often caused by substance abuse: divorce, teenage pregnancy, and incarceration.42

* * *

The point of listing these twenty-one problems is to show that drug and alcohol abuse affect society far more than we realize. Substance abuse truly is the modern world’s Pandora’s box; every social problem is linked to this disease.

Anyone who supports drug legalization should study this list and picture living in a world where all those problems are more common.

These twenty-one problems are why legalization is no small issue. I’ve seen victims of child abuse and domestic violence every day of my working life for thirty years. One of the main reasons for writing this book is that I can’t just watch Canada and the United States adopt policies that would make those problems—and nearly two dozen other social ills—even more common.

The legalization lobby avoids this side of the story, but each of these twenty-one social problems will get worse if we legalize drugs. On the other hand, recovery-based policies would reduce substance abuse and curb every one of these problems.

Given that choice, it’s hard to understand why there’s even a debate.

.

.

.

Endnotes

1. Matt Ferner “World Leaders Call For Massive Shift In Global Drug Policy” (Sept. 8, 2014) Huff Post Politics.

2. Connie I. Carter and Donald MacPherson “Getting to Tomorrow: A Report on Canadian Drug Policy” (2013) Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, page 7.

3. Canadian Drug Policy Coalition “Mission And Vision” drugpolicy.ca

4. Tony Newman “Beyond Marijuana: Gearing Up For the Battle to Decriminalize All Drugs” (June 20, 2013) Huffington Post.

5. Conor Friedersdorf “America Has A Black-Market Problem, Not A Drug Problem” (Mar. 17, 2014) The Atlantic.

6. The Economist “How To Stop The Drug Wars” (May 5, 2009) The Economist. Eugene Robinson “Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death shows that we’re losing this drug war” (Feb. 3, 2014) The Washington Post.

7. Doug Bandow “End The Drug War: The American People Are Not the Enemy” (Mar. 3, 2014) Cato Institute. David Godow “Are Sin Taxes on Marijuana a Price Worth Paying for Reform?” (Oct. 13, 2010) Reason Foundation. “Paternalism” Mercatus Center (Mar. 31, 2015).

8. Jeffrey A. Miron and Katherine Waldock “The Budgetary Impact Of Ending Drug Prohibition” (2010) The Cato Institute.

9. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University “Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population” (Feb. 2010).

10. Office of National Drug Control Policy Executive Office of the President “Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II 2012 Annual Report”.

11. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University “Behind Bars: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population” (Jan. 1998). The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University “Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population” (Feb. 2010).

12. Childhelp “Child Abuse Statistics & Facts” (2014) childhelp.org Caroline Wolf Harlow “Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers” (April 1999) NCJ 172879 Bureau of Justice Statistics.

13. Jason Ryan (ABC News) “Gangs Blamed For 80 Percent of U.S. Crimes” (Jan. 30, 2009) ABC News.

14. M.H. Swahn et al. “Alcohol and drug use among gang members: experiences of adolescents who attend school” (July 2010) Journal of School Health. National Gang Center “Frequently Asked Questions” (2014) nationalgangcenter.gov M.H. Swahn et al. “Alcohol and drug use among gang members: experiences of adolescents who attend school” (July 2010) Journal of School Health.

15. Joseph A. Califano, Jr. “High Society: How Substance Abuse Ravages America And What To Do About It” (Nov. 1, 2008) The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University.

16. Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights “Alcohol And Domestic Violence” (2014).

17. Daniel Brookoff, M.D., PhD “Drugs, Alcohol And Domestic Violence In Memphis” (Oct. 1997) National Institute of Justice.

18. “Buddy T.” (Alcoholism Expert) “What Are The Costs of Drug Abuse to Society?” (Feb. 28, 2014) alcoholism.about.com

19. H. Richard Lamb, M.D., Frederic I. Kass, M.D. and Leona L. Bachrach, PhD (Eds.) (1992) Treating The Homeless Mentally Ill American Psychiatric Publishing.

20. Ibid.

21. Legal Action Center “Making Welfare Reform Work” (Sept. 1997) lac.org

22. Kristen W. Springer et al. “Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women” (May 2007) Child Abuse & Neglect. D.A. Drossman et al. “Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders” (Dec. 1990) Annals of Internal Medicine.

23. S. Zierler et al. “Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection” (May 1991) American Journal of Public Health.

24. R.F. Anda et al. “Abused boys, battered mothers, and male involvement in teen pregnancy” (Feb. 2001) Pediatrics.

25. Joseph A. Califano Jr. (Letter to the Editor) “Alcohol, Drugs and Abortion” (May 25, 2007) The New York Times.

26. S.C. Martino et al. “Exploring the link between substance abuse and abortion: the roles of unconventionality and unplanned pregnancy” (June 2006) Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health.

27. Sarah C.M. Roberts et al. “Alcohol, Tobacco and Drug Use as Reasons for Abortion” (Aug. 22, 2012) Alcohol and Alcoholism.

28. N.P. Medora et al. “Variables related to romanticism and self-esteem in pregnant teenagers” (Spring 1993) Adolescence.

29. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration “The NSDUH Report: HIV/AIDS and Substance Use” (Dec. 1, 2010) samhsa.gov.

30. Mary Ellen Mackesy-Amiti et al. “Symptoms of substance dependence and risky sexual behavior in a probability sample of HIV negative men who have had sex with men in Chicago” (July 1, 2010) Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

31. M.H. Silbert et al. “Substance abuse and prostitution” (July-Sept. 1982) Journal of Pyschoactive Drugs.

32. Sharna Olfman (editor) “The Sexualization of Childhood” ABC-CLIO 2009 page 158. Or, page 158

33. Annalyn Kurtz “1 in 6 unemployed are substance abusers” (Nov. 26, 2013) CNN Money.

34. D. Henkel “Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010)” (Mar. 2011) Current Drug Abuse Reviews.

35. J.W. Bray et al. “The relationship between marijuana initiation and dropping out of high school” (Jan. 2000) Health Economics.

36. Christopher Ingraham “Study: Teens who smoke weed daily are 60% less likely to complete high school than those who never use” (Sept. 9, 2014) The Washington Post.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Feb. 14, 2013) “12th grade dropouts have higher rates of cigarette, alcohol and illicit drug use” (Press release).

38. Paul R. Amato and Denise Previti “People’s Reasons For Divorcing: Gender, Social Class, The Life Course and Adjustment” (July 2003) Journal of Family Issues.

39. DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B.D., & Smith, J.C. (Sept. 2010). “Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009.” Current Population Reports – Consumer Income. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

40. Hon. A. Ellen White and Craig M. Burshem “Problem Solving for Support Enforcement: Virginia’s Intensive Case Monitoring Program” (2012) National Center for State Courts.

41. Child Welfare Information Gateway “Grandparents Raising Grandchildren” (2006) childwelfare.gov

42. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry “Grandparents Raising Grandchildren” (Mar. 2011) aacap.org

Gogek, Ed. Marijuana Debunked: A handbook for parents, pundits and politicians who want to know the case against legalization. InnerQuest Books.